The pillars of liberal democracy are collapsing in many nations. “Liberty is under siege.”

Violent hate crimes have surged around the world, including the U.S., where disgusting racist, homophobic, and misogynist language has become normalized in political speeches and on social media, where violence has become routine, and where free speech and other democratic freedoms are under threat.

These realities highlight the fact that what sustains democracies is not simply legal safeguards and rules, but also social norms and practices, individual and communal ethics, empathy, excellent public education systems, and peaceful protest, including “calling out” racism and other social injustices “loudly and by name.”

As the authors of the 27 chapters in Artistic Citizenship document, artists of all kinds around the world are putting their art-making to work for social “goods” by “calling out” and protesting anti-democratic and anti-human behaviors.

(Note: By “artists” we mean amateurs and professionals in all the arts, arts educators, and students involved in art-making for active social justice).

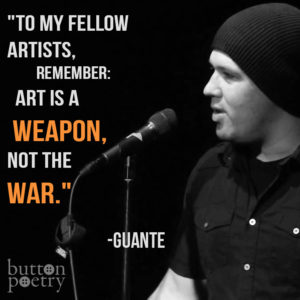

One example of a full-time arts activist is Kyle “Guante” Tran Myhre

Guante is a hip-hop artist, a two-time National Poetry Slam champion, an educator, a writer, and a contributor to Artistic Citizenship. He has “performed for justice” widely in the U.S. and abroad—from the United Nations, to the Soundset Hip-Hop Festival, to countless colleges, universities, clubs, theaters, and rallies across the U.S. His performances have been featured on BBC Radio 6-Music, MSNBC, Upworthy, Everyday Feminism, and Button Poetry. And he facilitates community workshops that use the arts as jumping-off points for deeper conversations about identity, power, empathy, and agency.

Here are two examples of Guante’s performances that exemplify his commitment to challenging dominant narratives related to race and racism, and deconstructing traditional notions of masculinity:

Many other examples by Guante and his colleagues are available on his website.

Takeaway Thoughts and Questions

Do arts educators have a civic responsibility to do more than talk-talk-talk about artistic “response-ability” and social justice in their journal articles and at conferences? Writing and face-to-face discussions are important, of course, which is why we applaud a 2017 initiative at Michigan State University titled “Musicking Equity: Enacting Social Justice Through Music Education.”

Hopefully, such conferences will actually lead to “enacting” social justice in the sense of actual participation in public contention, acting for social justice, doing it, performing it, and creating “ethical spectacles” of/for social justice.

As David has emphasized in several articles and conference papers over the last 10 years—see “Socializing Music Education“; “Artistic Citizenship as/for Music Education“; and “Canadian Music Schools: Toward a Somewhat Radical Mission“—“raising people’s consciousness about their oppression through reflection and talk is not enough: Physical and emotional support for actual participation in public contention is required” (Anyon). “Intellectualizing,” does not, by itself, move people—physically and emotionally—to take meaningful action for social justice.

To motivate people to join a social movement for meaningful resistance and positive change, it’s essential that they engage in some kind of action, as many scholars and activists have argued (Anyon 2005; McAdam, Tarrow & Tilly 2001; Meyer 2002; Payne 1995). The reason is that “people’s personal identities transform as they become socially active, and actions for social justice create new categories of participants and political groups: identities modify in the course of social interaction” (McAdam, Tarrow & Tilly). In Jean Anyon’s words, “One develops a political identity and commitment … from walking, marching, singing, attempting to vote, sitting in, or otherwise demonstrating with others.”