“Artistic citizenship” is a concept with which we hope to encapsulate our belief that artistry involves civic-social-humanistic-emancipatory responsibilities, obligations to engage in art making that advances social “goods.” The terms artist, artistry, and artistic as we use them are not elitist. By “artists” we mean to include people of all ages (from youth to adults) and levels of technical accomplishment (from amateur to professional practitioners) who make and partake of art(s) of all kinds, in contexts ranging from informal to formal, with the primary intent of making positive differences in people’s lives. Whereas artistic proficiency entails myriad skills and understandings, artistic citizenship implicates additional commitments to act in ways that move people—both emotionally and in the sense of mobilizing them as agents of positive change. Artistic citizens are committed to engaging in artistic actions in ways that can bring people together, enhance communal wellbeing, and contribute substantially to human thriving.

In framing this book’s project we invited contributors across art disciplines to share their research, their practical projects and strategies, their experiences, and their insights as artistic citizens. We deliberately left open the meaning of “artistic citizenship,” however, in order to allow a range of interpretations and perspectives to emerge. The result is, we think, an imaginative and inspiring collection of essays, richly suggestive in their range and scope. They address and explore quite a number of interlocking and provocative questions, including these:

- What does “citizenship” mean and how might these meanings relate to our understandings of the privileges and obligations that attend artistic practices?

- How might “artistic citizenship” differ from (or resemble) citizenship in general?

- “Is there a polity called art to which persons belong, owe allegiance, and derive benefits? If there is such a polity, what practices does being an artistic citizen require?”

- In what ways and to what extent do art-makers and art-takers have responsibilities (or obligations) to deploy the potentials of the arts to advance social justice, human rights, and the like?

- What personal, social, cultural, educational, political, therapeutic, economic, and health-giving “goods” can artistic engagements (amateur or professional) facilitate?

- What ethical issues and responsibilities attend the concept of art making as force for advancing positive social and political change?

- How might artistic citizens engage the “general public” in artistic projects designed to serve diverse public, social, cultural, political interests?

- How can ethically-oriented artistry contribute to the mitigation of racism, sexism, ageism, classism, and ethnocentricism, and other forms of social injustice?

- What abilities and dispositions of body-mind and heart do amateur and professional artists require if they are to engage in, develop, and expand the possibilities and potentials of artistic citizenship?

- What historical precedents can inform and refine our understandings of the “why, what, how, who, where, and when” of artistic citizenship?

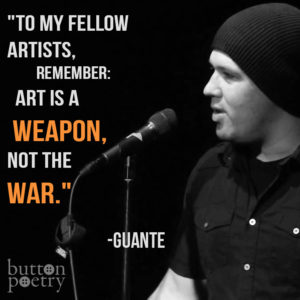

- What are the most effective strategies and tactics that artist-activists (or “artivists”[i]) to confront problems like racial violence, poverty, disease, discrimination, and the like?

- What are the specific or distinctive potentials of particular artistic endeavors for fulfilling the commitments and responsibilities of artistic citizenship?

- How can school and community arts education programs develop young people’s habits of heart and mind in and through socially responsible art making?

Additional questions and issues emerge from the chapters in the book, questions too numerous to list here. But the questions, discussions, and actions to which the book’s essays lead will be the ultimate measure of this project’s significance. We leave it to our readers, then, to carry these conversations forward—to follow the leads offered by contributors to this volume. Although we cannot know precisely the form those ideas may eventually assume, it is our hope that they will involve continuous critical dialogue across artistic disciplines about the ethical potentials of artistry, the nature of artistic responsibility, and the remarkable capacities of art to improve our neighborhoods, our societies, and our world.

[i] The concept of “artivism” and therefore “artivist” can be found in Rodney Diverlus’ chapter (in this volume) and also Chela Sandoval and Guisela Latorre (2007). Chicana/o Artivism: Judy Baca’s Digital Work with Youth of Color, in Anna Everett (Ed.) Learning Race and Ethnicity, (pp. 81-108), MIT Press.